Technology can be hard to accept, especially when it hints at our personal inadequacies. Perhaps that’s why some good ideas are a bit tough to swallow.

I admit that I’m not immune to having such hard feelings toward a piece of hardware. The first time I felt this way, it was about a camera.

My first real camera was a Canon A-1. Production lasted from 1978 through 1985, and it has gone down in the history books as a really groundbreaking piece of equipment. Even though it didn’t come from Canon’s professional ranks, this camera still raised the bar for the entire industry regarding microprocessor controls.

Don’t forget: If you go back a few decades, cameras were devoid of computer chips and little black boxes. If a battery was present, it just operated the light meter. For the most part, these were fairly simple machines by today’s standards. Focus and exposure were all handled manually.

If I had to guess, I got my A-1 around 1983 or so. I was in junior high and my dad, also a photo buff, figured I was ready for a serious camera. He also had an A-1, but mine came courtesy of the used market.

My A-1 faithfully served me through high school and into my first year of college, the corners of its body picking up patina as the plastic wore away to reveal the metal below. Unfortunately, technology eventually caught up with the A-1.

Cameras made huge leaps during the 1980s, and Canon basically rebooted their SLR model line starting in 1987. The new line was known by the EOS name—their latest digital cameras are part of the same family—and one of the biggest changes was a new lens mounting arrangement.

It wasn’t that I fell under technology’s spell, but if I wanted to add more lenses and accessories to my bag, I needed to upgrade. The new lenses didn’t fit the old camera. I was basically running an unsupported platform.

My parents took me camera shopping sometime in 1989. I can’t remember the store, but something wants me to say that it was on Route 110 on Long Island. What I do remember is the moment the salesman handed over the new EOS.

It was sleek and modern. Looking back, it was kind of like a Miata vs. an MGB. Sure, both will yield open-air fun, but obviously one is a later incarnation.

Functional upgrades, the salesman explained, included new shooting modes, LCD display, faster shutter speeds, built-in film winder and autofocus. And right there I started to lose interest. “We don’t need no stinking autofocus,” I said to myself. “I’m a seasoned photographer. I have already been through one full year of college. Of course I know everything.”

If there was a saving grace, it was a small button found on the barrel of the lens: The autofocus could easily be switched off.

I saw autofocus as something unnecessary that also added weight, cost and complexity. On the other hand, there was no way to get away from it. Autofocus had become an industry standard, just like fuel injection and radial tires. I was eventually the proud owner of a brand-new Canon EOS 630 and matching lens.

The kicker to that story: I don’t think I ever used the manual focus mode. Autofocus let me do all kinds of cool things, like shoot with the camera held high above my head or down on the ground. I could also pop off photos more quickly—just compose and squeeze. Call me an instant convert.

Who knows how many photos I have shot since that day 21 years ago. A million? A zillion? A kajillion? Okay, maybe it’s a more manageable number.

One thing I am sure of is that the autofocus rarely let me down, and through the years it has only gotten better, faster and lighter. At the same time it has offered more control. The latest Canons offer 45 focus points, which is 44 more than my first EOS had.

The dual-clutch transmissions showing up in so many showrooms may be the automotive equivalent of autofocus. These new transmissions have many benefits, yet are taking some heat from the hardcore enthusiasts. The complaints include the added weight, cost and complexity—all arguments I have heard before.

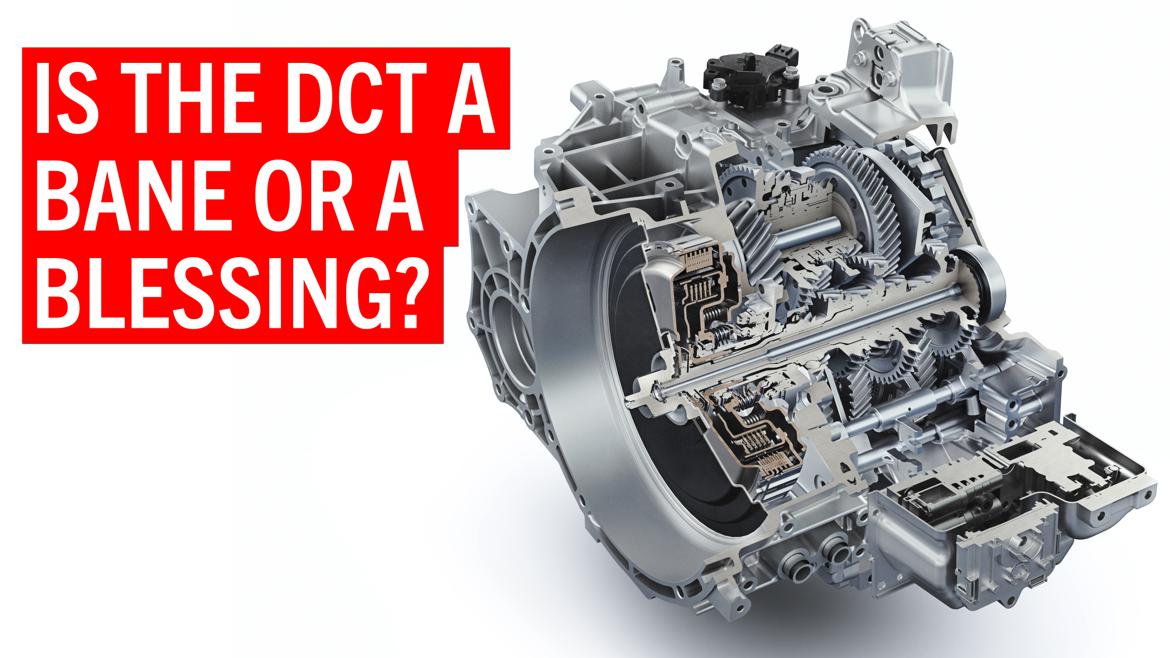

The dual-clutch transmission is an engineering marvel. Odd gears are housed on one input shaft, while the even ones live on the other. Each input shaft gets its own clutch, hence the dual-clutch designation.

This arrangement allows gears to be engaged before they’re needed. When the time comes to shift gears—bang—it happens right away. The gearbox’s ECU knows what is going on and the time needed to switch between gears is measured in milliseconds.

Manual control is also possible by using buttons mounted on the steering wheel and/or a lever that more or less resembles the traditional stick. However, there are only two pedals: stop and go. The traditional clutch pedal has been dismissed.

I think some of the bad rap comes courtesy of the sins delivered by the traditional automatic transmission, which in our automotive world has only really been favored by Jim Hall, drag racers and those campaigning F Stock Camaros. Aside from limited examples, for the most part automatic transmissions have been associated with slow performance, a limited number of gears, and not much manual control.

Oh, how technology has drastically changed things. Yes, dual-clutch transmissions are heavier, pricier and more complex than the traditional stick shift, but there’s no denying that these new boxes offer quicker acceleration as well as better economy. Hey, let’s face it, a computer-controlled, seven-speed gearbox will generally outperform five or six gears being rowed by a human.

Where can you find this new technology? All over. It’s the only transmission type offered in the Nissan GT-R as well as all current Ferrari road cars. Porsche is quickly making it available in nearly their entire model line, while VW and Audi have shown that this kind of hardware isn’t limited to cars north of six figures.

I wonder if there’s a deeper issue fueling this ire, as gearheads rarely pass up something that makes them faster: It’s tough to admit that technology can best us at something that’s seen as a core element of a favorite activity. Rowing up and down the gears has been an integral part of sports car ownership for decades, and few are willing to hand that over.

Just like ABS, fuel injection, windup windows, automatic chokes, overhead cams and electric starters, dual-clutch transmissions may take some time to catch on among the hardcore drivers. However, I think I can see the attraction.