Click the image below to watch one of our runs at the Wolf Ridge Hillclimb.

To enhance the experience, put on your racing helmet while watching the run.

Photography Credit: Per Schroeder

[Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the May 2008 issue of Grassroots Motorsports.]

Gravity just won’t leave us alone. From the womb to the tomb it tugs at us, pulling us down toward the center of the Earth. Rather than lie down and give up, however, clever humans have found plenty of ways to thwart gravity, and even to play with it.

We tease gravity a little bit every time we jump. We make thrill rides that exploit it and airplanes that defy it outright. A few lucky folks have had the opportunity to hurtle through space and escape its effects altogether.

Heck, we’ve developed to a point where even a standard street-going sports car can generate lateral forces that exceed the constant downward pull of the Earth. Take that, gravity!

Of course, gravity gets us back when we’re learning to drive a manual transmission. Inevitably, we get stuck at a red light on a steep uphill grade with a rusty garbage truck just millimeters off our rear bumper.

Still, once underway, it’s hard not to get a kick out of cheating gravity with a simple stab of the throttle on a good uphill stretch. The slope of a good, steep hill enhances the sensation of being pushed back into the seat, and most climbing roads tend to be of the delightfully twisty type. There’s beauty, danger and thrills in them thar hills.

For more than a century—nearly as long as the automobile itself has been around—drivers in search of a challenge have been competing in hillclimbs. In the late 1800s, getting an automobile up a hill was quite a feat in itself, never mind how long it took. Man and machine were put to the test on primitive mountain roads, and early marques like Stanley, Hudson and Duesenberg climbed to the top of the time sheets.

Before World War II, a number of hillclimbs enjoyed huge popularity, not unlike NASCAR today. Factory teams from the U.S. and Europe would send their top cars and drivers to compete at events like the Giants Despair Hillclimb in Pennsylvania, where massive crowds of more than 50,000 people would cheer their favorites up the hill. In America, Pikes Peak became the biggest of all, and it was synonymous with the legendary Unser family in the 1920s and ’30s.

Photography Credit: Richard Hunter

World War II had a major impact on the automotive industry, and it forced many motorsports to the back burner for a few years. Fortunately, U.S. hillclimbing enjoyed a renaissance here in the States starting in the late 1950s. The spectator draw wasn’t quite as high as it had been before the war, but plenty of notable drivers, including Carroll Shelby and Parnelli Jones, tried their hand at the man versus mountain format.

The boom in amateur club road racing events in the 1960s and ’70s was echoed by an influx of club-level cars and racers at hillclimbs. Several drivers rose to fame among their peers, including Georgia’s Ted Tidwell and Pennsylvania’s Oscar Koveleski. They came to the mountains armed to the teeth with impressive machinery ranging from ultra-lightweight Porsche 904s to monstrous McLaren Can-Am racers.

Since the late 1990s, the popularity of hillclimbs has waned. While regional events enjoyed triple-digit driver attendance in the 1980s and early 1990s, a more likely draw these days is closer to 50. Several key events have vanished completely, including the famous Mt. Washington Climb to the Clouds and the Chimney Rock Hillclimb.

Declining attendance and the loss of several high-profile events have inspired many hillclimb proponents to step up their enthusiasm and do something about it, particularly in the Southeast. In the past few years, a number of new hillclimbs have sprung forth, and they’re generating fresh buzz for this historic form of motorsport.

In 2005 the Tennessee Valley Region SCCA held the inaugural Crow Mountain Hill Climb in Northeast Alabama. The Central Carolina Region SCCA followed suit with a pair of new events in 2007: the Wolf Ridge Hillclimb and the Rock-n-Road Hillclimb at Eagles Nest.

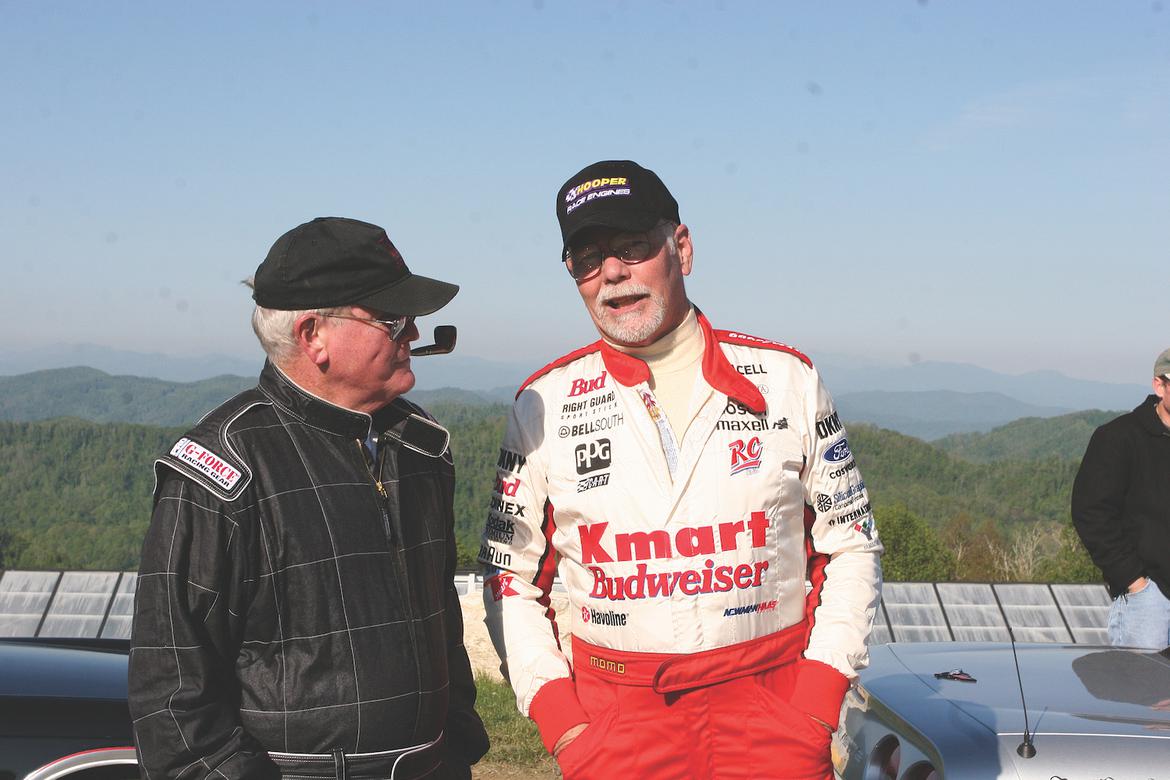

Hillclimb veterans George Bowland and J.K. Jackson (complete with pipe) have been tearing up hills on the East Coast for decades. Bowland’s BBR Shark is a mess of wings and horsepower that typically sets the fastest time of the day. Sunsets at hillclimbs are usually quite beautiful. Photography Credits: Scott R. Lear

We were invited to participate in the first-ever Wolf Ridge Hillclimb, held north of Asheville, N.C., on May 19-20, 2007. Like many uphill events, Wolf Ridge’s venue is a ski resort that offers private roads, meaning little disruption to local traffic. The course is nearly two miles in length, with 800 feet of elevation change from start to finish.

Event chairman Tony Wentworth was brimming with excitement about the brand-new venue as he extended the invitation, and we couldn’t help but find his attitude contagious. It had been several years since we’d hillclimbed one of the GRM project cars, so we decided to re-immerse ourselves in the world of vertical ascent.

Wolf Ridge is an SCCA-sanctioned hillclimb, so our first order of business was to make sure our SCCA Time Trial license was up to date. Due to the potential dangers, SCCA considers hillclimbing to be the top tier of their Time Trial program. As a result, hillclimb drivers must have proved their competence behind the wheel to the satisfaction of the SCCA, and they are required to wear head-to-toe safety gear, just like road racers.

Like the personal gear, the required level of safety preparation for the car also depends on which type of Time Trial competition the driver is planning to run. In order to compete at a hillclimb, the fastest cars and those with open cockpits must have a full cage, while a full roll bar is the minimum for anything else.

Our project Honda Civic Si was a great car for our first hillclimb in a while, with gobs of safety, good handling and not quite enough power to get us into trouble. Photography Credit: Richard Hunter

Since our trusty 2002 Honda Civic Si is fully prepared for road racing, it was a natural choice for the event. We have no reservations about exceeding minimum safety requirements, particularly when there are huge freaking rocks just inches from the racing line. The full cage, fire bottle, and robust seat and harness combination in the Civic are way more comforting to us than a fuzzy blanket ever was.

[Building a Road Racer in Eight Easy Steps]

The rest of our checklist contained the items we usually bring to a road race. That included our jack, some jack stands, a spare set of wheels and tires, our in-car video setup, an assortment of common hand tools and our tire pressure gauge. We brought a fuel jug, but we didn’t end up needing it despite the generous number of runs. Hondas just don’t burn that much gas in two miles.

The entry fee for the average hillclimb is less than $200, and that fee commonly includes a banquet. Ours was held at The Lodge at Wolf Ridge, a massive, rustic building that serves as the hub for the ski resort and was the home base for the event. The Lodge was doubly important since it was the most convenient place to grab food all weekend.

When packing for a hillclimb, remember that you might be spending quite a bit of time in high altitudes. It can get cold up there, even in the summer. Bring warm layers for the mornings, and keep some energy-giving snacks handy in your paddock bin so you don’t have to demonstrate your survival skills by eating your driving shoes between runs.

Part of the fun and the challenge of hillclimbing is that every venue is unique. In some ways it’s like an autocross, as it’s up to the driver to memorize the course. Also like an autocross, the best run counts. On the other hand, there are many more turns to memorize than the typical autocross, and the speeds and the dangers are similar to what you’d find at a full-fledged tarmac stage rally.

The majority of modern hillclimbs are run on asphalt (with the notable exception of Pikes Peak, which is about half paved and half dirt). With a dry forecast and a fully paved surface waiting for us at Wolf Ridge, we opted to run the medium (C50) compound Hankook Ventus RSS Z211 tires that we’ve been using for road racing.

A key point gathered from the drivers meeting was to take it easy early on and get to know the course and the conditions before trying to squeeze out that final tenth of a second. We’re fans of this advice in road racing, since there’s no worse way to start a weekend than finding the wall in the first corner after the green flag.

The Lodge at Wolf Ridge served as our rustic home base and primary food stop. Photography Credit: Scott R. Lear

The blind corners and confined spaces of a hillclimb make the reconnaissance run even more critical. At Wolf Ridge, we were told that our first run wouldn’t count anyway, so there was no sense in treating it as anything other than a speedy course walkthrough.

Learning a hillclimb course is an exercise in danger priority assignment. During our untimed run we focused on identifying the corners that would not hesitate to kill us. There were two such corners at Wolf Ridge, one lined by a really big, car-smashing rock and the other featuring a decreasing-radius turn bordered by a steep slope.

After the recce run, we did our first timed run at about 80 percent attack, feeling out the course in some of the faster areas and making sure we had the car plenty under control before coming to our designated hazard zones. We were rewarded with a time of 2:18.829.

As we started giving the Honda longer doses of full throttle, we began to appreciate how steep the mountain really was. Our Civic Si, which has a decent amount of punch from its 2.0-liter, 160-horsepower VTEC engine, could barely accelerate in third gear, even on the shallower straights. Fortunately, second gear tops out near 60 mph and was well-suited to most of the course. We also found that grabbing first was an advantage in the two tightest hairpins.

The Hankooks had plenty of bite on the rising asphalt, and every little dab of the brakes was magnified by the hill. For most corners, simply lifting off the throttle was enough to shed speed thanks to our combination of moderate power and good grip.

By our third and fourth runs, we found ourselves starting to think ahead as the mountain road became more familiar to us. We had our braking zones worked out for the really dangerous areas, and we were starting to recognize the second- and third-tier dangers so we could maximize speed around them.

With more than five runs under our belt on Day 2, we were actively hunting for more speed. We minimized our braking zones, clipped apexes a bit closer to hazards and, in a few key corners, tested our bravery beyond the edge of the pavement. By our final runs there didn’t seem to be much left in the car. Our final two attempts were within 0.007 second of each other, with a fastest time of 2:10.863.

That was good enough to make us the fastest front-wheel-drive car on the hill. For comparison, Mark Mashburn drove his A Street Prepared Chevy Corvette to a fastest fendered time of 2:03.164, and George Bowland’s A Modified BBR Shark—a contraption that’s basically a bunch of wings, a high-powered snowmobile engine and some sticky tires—terrorized the hill to set FTD with a 1:47.203.

There’s no denying that hillclimbing is a serious rush. It occupies a unique place in motorsports, mixing elements of autocross, time trial and stage rally with the time-honored tradition of tearing up a winding mountain road as fast as you dare.

The cost per minute of run time is similar to what you’d find at an autocross, but the thrill is undeniably greater. Unfortunately, so are the risks, so hillclimb your daily driver only if you have a backup plan for getting to work on Monday.

If you’re on the fence about running a hillclimb, consider spectating or volunteering at one first. The beautiful scenery at one of the resort-based events makes for a great weekend getaway for couples.

Hillclimbing may have faded from its former glory, but that just means the lines aren’t as long right now. It’s simply too thrilling a form of racing to allow it to slip into obscurity.

View all comments on the GRM forums

You'll need to log in to post.