We’ve all seen them: giant, lumbering behemoths. They groan and struggle and sway, desperately clinging to what little stability they have.

No, we’re not talking about overweight dogs or someone’s pet hippo. We’re talking about dangerous truck-and-trailer combinations, and anybody who’s walked the paddock at an amateur race track …

Explorer or Exploder?

There’s only one way to truly convey what can happen when towing goes wrong: Tow improperly, then provide gratuitous pictures and video of the aftermath.

With this mission in mind, we needed a tow vehicle, a trailer and a car to tow. This meant deciding what sort of towing setup we would use. Most of us don’t use an 18-wheeler to get our car to the track, but many gearheads do have rigs that are a little more heavy-duty than the aforementioned sedan.

We decided that a midsize SUV and an open trailer would be representative of the average enthusiast’s tow rig.

We fired off an email to a manufacturer of premium European driving machines.

Their SUV would be a perfect choice, we reasoned, and its excellent rollover rating assured us that our test driver would live to tow another day. They’d be idiots to not let us borrow (and possibly destroy) one of their modern SUVs, so we were confident they’d say yes.

And, surprisingly, the company replied the very next day. Their answer? “While we’d welcome exposure in your publications for the unheralded towing capabilities of the [SUV], this does not feel like the right fit, so we’re going to pass on this one.”

Darn, and we were sure that would work. On to Plan B: Roam Craigslist with a wad of cash and a blatant disregard for good sense. We embarked on a marathon Craigslist search, looking at three SUVs in a single night. By 11 p.m., we’d purchased our test mule, a 1997 Ford Explorer.

It had bald tires, a cockroach infestation, and a smattering of bent sheet metal and broken interior parts. A new European SUV it wasn’t, but it was mechanically sound. Plus, it came with the stigma of being a Ford Explorer–perfect for a test involving evasive driving maneuvers and lots of weight on the rear tires.

We stripped the interior and installed a roll cage, race seat, trailer hitch and electronic brake controller. Things were about to get interesting.

Trailer Time

Next, we needed a trailer. Fortunately, Best Price Trailers is located across the street from the GRM offices. Robin Hanger found the perfect one for us: an 18-footlong, dual-axle, all-steel model. Weighing in at 2100 pounds, it was perfect, if not a little overkill, for the average club racer. We promised to bring back whatever remained of the trailer after our test.

The Finishing Touch

With a truck and trailer procured, it was time for the final piece of our 12-wheeled puzzle: a trailer weight.

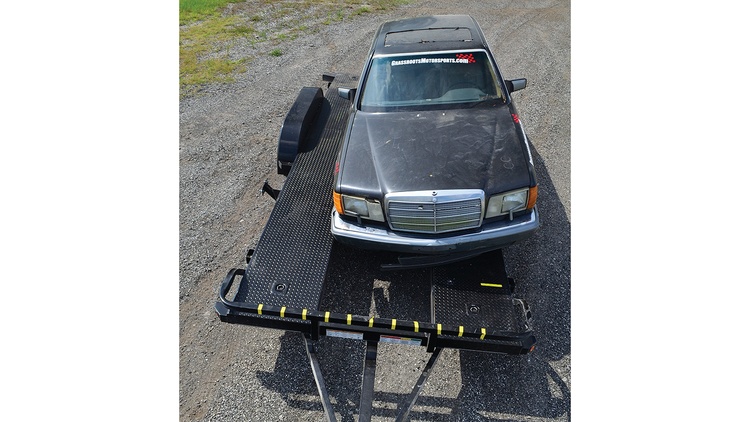

Our Explorer was rated to tow 6200 pounds, and naturally we wanted to load it to its limit. So, we needed a roughly 4000-pound object to strap down on the trailer. Bonus points if it was vaguely carshaped– after all, few people tow cubes of lead to the track every weekend. After rummaging around in our backyards, we found the answer: a 1985 Mercedes-Benz 420SEL that was originally purchased as a parts car.

It was, in one word, perfect. Four wheels? Check. Car-shaped? Check. Weighs nearly 4000 pounds? Check. After a few hours of coaxing with two trucks and a winch, we managed to get the Mercedes strapped onto the trailer.

Test Track

Every day, people have dangerous crashes while towing trailers on public roads. Though it would have been cheap and easy, we decided that the highway probably wasn’t the best place to push our rig to its limits. Instead, we conned the beautiful Florida International Rally & Motorsport Park in Starke, Florida, into letting us crash on their property.

They were even kind enough to let us borrow their chief instructor, Bryn Walters, who bravely volunteered to play the role of test driver. Finally, we were ready to see what happens when towing goes wrong.

TEST 1: Baseline

A drive through our test course without a trailer.

When the morning of the test came around, we strapped Bryn into the Explorer’s Ultra Shield seat and sent him out for test number one: a baseline run without anything hooked to the truck.

To measure the rig’s performance, we put together a test track that mimicked the worst stretch we’d encountered while towing a trailer on public roads: two hairpin turns with a straight and a section of esses between them. Finally, there was a panic stop from 50 mph.

After laying down a few laps to get comfortable, Bryn reached a verdict: “Well, it’s a truck. Nothing real exciting here.”

TEST 2: Loaded Trailer

Towing a properly loaded trailer.

Now that we knew what a stock Explorer could do, it was time to hook up the trailer. We wanted to see how much the driving dynamics changed just by adding a correctly configured towing load.

So, we hooked up the loaded trailer and sent Bryn out for another round of tests. The Explorerand- trailer combination was slower to react and took longer to stop, but it generally drove like you’d expect a small truck towing a big car to drive. Bryn again reported no surprises.

TEST 3: No Trailer Brakes

Towing without trailer brakes.

It was time to start turning up the knobs, so we started with the most common towing sin we’ve seen in the paddock: broken or missing trailer brake systems.

Once a loaded trailer reaches a certain weight (3000 pounds in most states), it’s legally required to have trailer brakes. The most common form of trailer brakes are electromagnetic drums that are actuated by a trailer brake controller in the tow vehicle. These simple devices use an accelerometer to gradually apply the trailer brakes when the tow vehicle slows.

With all this in mind, we unplugged the trailer brakes and wished Bryn good luck. Then we found a sturdy Jersey barrier to stand behind.

Bryn handled the Explorer well, though it was clear that trailer brakes do make a difference. His stopping distance was far longer–186 feet versus the 174- foot baseline. Additionally, he said the trailer acted like a pendulum under heavy braking, trying to push through the stopping truck.

While slowing the truck-and-trailer combination looked like an exercise in puckering, Bryn controlled it like a champ. He also praised the Explorer’s ABS, saying it was a big help in preventing the trailer from pushing the truck around too much. Sadly, he hadn’t yet wrecked.

TEST 4: High Tongue Weight

Towing with the car too far forward.

Bryn, the Explorer and the trailer had shown that they could handle a little adversity, so we hooked up the brakes again and tried something a little more extreme. We pushed the Mercedes all the way to the front of the trailer, bottoming out the Explorer’s suspension and making the hitch groan and bend.

This particular setup may have been a little excessive, but having too much weight on the tongue of a trailer is an exceedingly common mistake. It can overload the rear of a vehicle, causing unpredictable handling and lessening the effect of any steering inputs. We’re pretty sure we saw the front wheels of our Explorer leave the ground at one point, and Bryn described this combination as “wobbly, like a dog wagging its tail.”

Unfortunately, professional rally instructors are pretty good drivers, so this test didn’t produce very spectacular consequences. Bryn’s lap times and stopping distances didn’t change much–remember, he’s a trained professional–but he says that the pucker factor had gone up tremendously. Unless you enjoy seeing air under your front tires, we suggest limiting your trailer’s tongue weight. Aim for 10 to 15 percent of the total trailer weight.

TEST 5: High Tail Weight

Towing with the car too far rearward.

At this point, the Explorer’s hitch seemed sufficiently exasperated from being dragged along the ground, so we backed up the Mercedes–a lot–until it was nearly falling off the rear of the trailer. Now, instead of having more than a thousand pounds of tongue weight, we had none at all. In fact, the trailer was actually lifting the back of the truck.

Anyone who’s ever towed a rear-engined car that’s pointing forward knows this sensation. We also have to admit that towing a Porsche 911 with a minivan nearly cost us our lives many years ago.

Fortunately, we weren’t in the driver’s seat this time–Bryn was. We sent him out on track and returned to our favorite Jersey barrier.

And wow, were we ever glad there was concrete between us and our creation. Bryn didn’t mince words after those runs: “There’s only one word for that: evil!” Even from outside the rig, we could see he wasn’t having any fun. The Explorer tried to spin with every turn, and Bryn was essentially drifting through the curvy part of the course.

Once he finally got to the straight, he floored it– only to spin the tires at the SUV’s barely weighted rear. At full speed–in this case about 45 mph–the whole truck-and-trailer combination slithered like a snake, sliding rhythmically across the pavement. Unfortunately for Bryn, the truck’s rhythm was always out of sync with the esses, meaning he had to slow significantly and basically idle through them.

TEST 6: Flat Tires

Towing with poorly inflated tires.

We were starting to realize that you can get away with almost any towing sin if you’re a pro rally driver, so we called in Bryn, moved the Mercedes to its proper position on the trailer, and flattened all the tires. Seriously? Yes, seriously.

We wanted carnage, and properly inflated tires were standing in our way. Every tire–on both the Explorer and the trailer–was lowered to 15 psi. We figured that was the lowest pressure the average human would see and still think, “Eh, that tire’s not flat. It’ll be fine.”

While we were letting out the air, we realized that a few of the Explorer’s tires had big bulges in the sidewalls. These are usually indicative of imminent failure, so we smiled, wished Bryn well, and sent him out for another round of tests.

Driving, never mind towing, with soft tires is a recipe for disaster: Besides the reduction in control and poor handling, low tires tend to overheat on the highway, and lots of heat is a common cause of blowouts.

Annoyingly, Bryn seemed to have that loss of control under, well, control. He did start clicking off laps that were slower than usual, though–by about 2 seconds per lap–and he was working much harder than before. “Mushy and uncertain” is how he described this session.

The rig was working more, too. Each time it went through the esses, the trailer tires deflected from one extreme to the other–figure more than 4 inches total.

No blowout, though, as the tires stayed mounted on the rims. Don’t forget, our rig and trailer only had to handle a few laps at a time, not hours on the interstate. We were going to have to try something more drastic in order to get our money’s worth from that roll cage.

TEST 7: No Shocks, Car on Backward

Towing without rear dampers and with the car facing backward on the trailer.

Okay, time to recreate some horrors–all in the name of science, right? We disconnected the rear dampers and put the car on the trailer backward. Don’t worry if you’ve done this before. We’re not here to pass judgment.

Bryn’s next few laps confirmed our suspicions. He returned sporting a full mane of white hair and babbled something about seeing scary things.

Bryn, a professional, was able to keep the rig on the course–just barely–but he led the dance for a limited number of laps. Could he have survived 7 hours on the interstate? Not likely.

TEST 8: No Tie-Downs

Towing without the car strapped down.

At this point, it was getting late and we were getting tired of Bryn’s competence, so we threw him a curveball. Cheap tie-downs, the kind most people tow with, break all the time. To simulate this scenario, we simply removed all the straps holding the Mercedes to the trailer. Oh, and instead of driving our normal test loop, we told Bryn to use the bumpy gravel that lined the outside of the track.

One of us might have yelled, “Thrash it like a rented Hyundai!” Hey, it was the heat of the moment–cut us some slack.

We were expecting greatness from this test, and we weren’t disappointed. The Mercedes galloped into the air like a mighty thoroughbred, then came crashing down on the trailer’s left fender like a sumo wrestler. This pushed the fender into the trailer’s tires, and plumes of white smoke quickly enveloped the Benz.

Bryn kept driving, the truck and trailer now fishtailing in the gravel. The Explorer seemed constantly on the verge of doing a barrel roll, and the run only ended when Bryn eventually lost control and the rig jackknifed.

Jackknifing a trailer carrying an unsecured car isn’t exactly a gentle experience. The Mercedes kept moving long after the truck had stopped, finally coming to rest in the Explorer’s left-rear quarter panel.

Finally, we’d seen the disastrous consequences of improper towing. We extricated Bryn from the creaking, smoking pile of machinery, thanked him for a job well done, and started the cleanup process.

Sometimes Towing Goes Wrong

So what did we learn? Like most things involving a car, towing one safely comes down to being a skilled, alert driver.

Bryn was able to get away with murder on the equipment side of things because of his driving skill. However, most of us are not professional driving instructors, and none of us tow our cars to the track on, well, a track. We tow on public roads full of lousy drivers.

As these tests showed, a subpar trailer puts much more strain on the driver. Add in one unexpected issue, and that marginal rig could quickly end up in a ditch–or worse.

Towing Takeaways

Tongue weight should be 10 to 15 percent of your total trailer weight–no more or less. If 10 percent of the trailer’s weight exceeds the tongue weight rating for your tow vehicle, don’t tow with that vehicle.

Trailers are fairly simple machines, so there’s no excuse for not maintaining them.

Don’t have time to maintain your trailer? Just pay somebody–trailer repairs are priced far below Ferrari repairs. What’s worse, a $100 trailer repair bill or causing a “CHiPs” accident?

If something does go wrong, be gentle and gradual with your driving inputs. Often the best solution is to come to a gradual stop.

When in doubt, add redundancy. This goes for wheels, straps, safety devices and so on. Always use at least two tie-downs on each end of the towed car. We favor Mac’s.

If you can’t figure something out, call a professional like Best Price Trailers. Dealers are usually happy to help, even if you didn’t buy a trailer from them.

![]()

![]()

![]()