Arrow time!

Here are some arrow making tools:

The blue thing is used to shave the arrow to accept glue on points and nocks (the back, what clips onto the string). thing that looks like a large stick of hot glue is exactly that, (called arrow point glue, but it's just hot glue), and the other stuff is self explanatory. I also use super glue (for nocks) and artificial sinew, which is just nylon string colored to look like sinew. For arrows, get the finest string you can. I think mine is called 15#

After figuring out which spine weight you want, get some arrow shafts. They come by the dozen in ranges of 5#. Sometimes they are weight matched, sometimes not. Many people prefer port oxford cedar, and there's nothing wrong with that. I went with sitka spruce, because it is claimed to be a bit tougher. It doesn't smell as good, but I don't often smell my arrows. I do, however, break them, and I don't want to. Sitka spruce is also farmed because it grows so fast, and port oxford cedar is not. Therefor, POC is disappearing, and sitka spruce isn't. I guess that makes it more 'green'? I realize the irony of owning a rotary powered car and claiming something I do is green. I really just got it because of the strength.

First, make sure they are all the correct length. finished arrow length is usually measured between the nock and the point, not from the point to the nock. Remember the taper tool will take some of the length away from the raw shaft. make sure you know how much, and cut the shafts accordingly. For me, I left the test arrows full length, and i'm making these the same length (remember, differing lengths change dynamic spine weight) Here's what the end looks like:

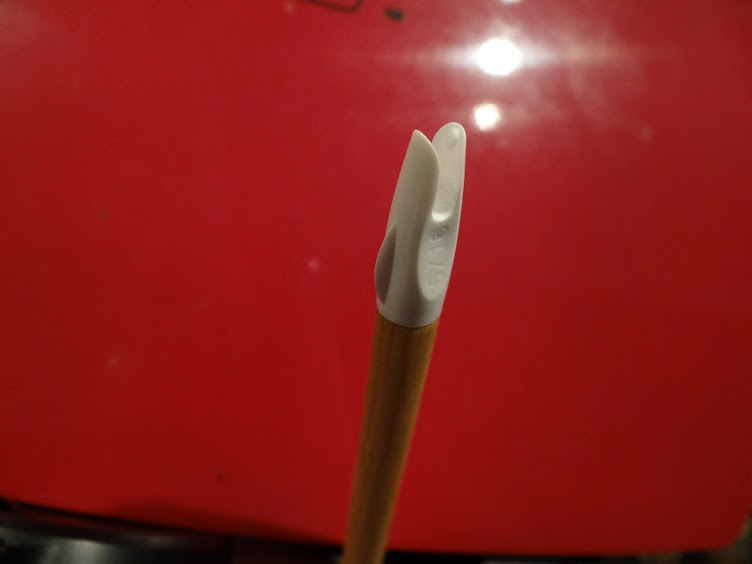

I put the nock on first. Take the blue tool, and use it like a pencil sharpener. The steeper angle is the nock, the other is for points. you'll notice the nock has a bump on it:

When the arrow is clipped on the string, that should point toward your body. What I mean by that is if you hold the bow with your left hand and the string with your right, it should go left of the string. You should put it on the shaft such that the growth ring lines go horizontal when shooting (perpendicular to the string). One more 'traditional' way of doing it is to cut the nock right into the shaft. This is called a 'self nock.' I've done this, and it takes too much time. I want to shoot, not file nocks.

Now the tips! I actually did this last, but it's more related to doing nocks, so whatevs. Here's a shot of the shaft shaved down before gluing:

It's a bit rough, but that's because I need a new point taper tool. I once made some arrows out of oak and the blade wasn't really up to it... So! Get the glue hot and melt-y with the candle. More is not more here, don't burn the glue, just melt it.

Then, smear some on the shaft

That ended up being way more than needed, but the last time I was at the range I lost an arrow inside a target, so call me paranoid if you want. Now, keeping the tip not far from the candle (to keep it from cooling off), heat the tip over the candle using the pliers

After this, push the tip on and spin it. This will distribute the glue evenly, and thanks to the exacting nature of the arrow taper tool, it will center and straighten the point. If the glue isn't hot enough and you can't do this, put it back over the candle and then redo this. Some glue will squeeze out, that's ok. Quench it in water, and then shave off the excess glue.

Now, the feathers! When you buy feathers, they look like this:

In the past, you could get 2 fletches per feather, but not anymore. They use flight feathers from turkeys that are raised for food. People buy smaller turkeys now, so they kill them younger. Shorter feathers, only 1 fletch per. Sadly. Feathers are sold by left or right "wing." There's some more old tyme lore about which one you need, but in reality, just make sure all of them are the same. I think mine are left wing? It doesn't matter because they are ALL left wing. Now, mine aren't glued down all the way, they are wrapped old school style. Also, it's cheaper style, because fletching jigs aren't free. To facilitate this, I start by peeling off the first half inch or so of the feathers. Start by grabbing a little, and pulling it forward like so:

It'll peel right off nice and easy. Now, a certain distance back (in my case 4.5") bend the feather a little and separate the thingies:

Do what you did in the front of the feather the the ones after the bend. Be careful not to rip up the feathers in front of the bend.

Peel the rest off. You'll have a really long stick out the back. The feather you have is much higher than it should be unless you want flu-flu arrows, which are used for birds/small game. The tall feathers slow the arrow down, so it won't go right past the squirrel and into the woods 100 yards away, never to be seen again.

Cut the shape you want. then, do it exactly the same on the other feathers. Here's what I do:

This isn't the result of personal preference, though I like the looks, it came about through trial and error. A common feather type is the shield cut:

With this design, the tines or whatever they're called are really short on the leading edge. Many self bows are braced lower than mass produced recurves, so the feathers may touch your hand. when you then pull the string back, they get bent backward. This damages the feathers, makes noise, and doesn't feel good. The long leading edge on mine instead lays flat against the hand. The back end it cut in like that because i shoot 1 above, 2 below. Basically, with my middle and right fingers below the arrow, and my index finger above. Some shoot all 3 fingers below. Feathers that stick way back will mess with your fingers (and face) at full draw.

They are different colors, white and blue in this case. 2 of them are blue, one white. Having one odd one is normal. it's called the 'cock' feather (heh). Remember the bump on the nock that sticks out? that's where the white one goes. The blue ones are evenly spaced, such that when the arrow is on the string, they face kinda up right, and kinda down right. The white one sticks out left (assuming you shoot right handed, like most people).

I attach just the front of the feathers with a drop of super glue:

Notice the natural twist? Yeah, i'm gonna use that. It's called "helical" fletching. You can also do it straight if you want, but that's not as easy without a fletching jig. Think of it like rifling on a gun barrel, this makes them spin.

Now, pull the feather back so there isnt' a gap between it and the wood, and apply a drop of super glue where it touches the back of the wood part. At this point i trim off the long spine sticking out the back, and the feathers are each barely secured with a drop of glue on both ends. It's important to get the twist even on all 3 feathers, and then on all the rest of the arrows.

Now, take a knife or something and try to taper the leading edge of the feather down to wood. This is especially important if shooting off your hand. Then take the atrificial sinew (or whatever you use) and glue a the start to a feather like so:

Wrap tightly forward on the shaft, and then start wrapping tightly back

When you get to the feathers, you can spread out the way it's wrapped, separating the feathers to slide the string through, then reattaching them. Then, at the back, return to tightly wrapping until you get it nice and secure, and then secure it with another drop of super glue.

Sorry I don't have more pics of that process, but it takes both hands until it's done. Notice the spiral nature of the feathers:

It doesn't take much to make the thing spin very quickly.

Simple enough, right? Ok now do it again a dozen times, exactly the same way.