Something in your engine will break, wear out or require an upgrade, forcing you to—gulp—pull a cylinder head. This job can be quite overwhelming and complex, especially if you’re working with an overhead-cam engine, but it’s much less intimidating when you break it down into steps.

One of the cars in our fleet, a 1988 Alfa Romeo Graduate, recently needed some headwork. Had this been a Miata, Honda or other modern DOHC engine, we’d have gone about the repair the same way.

Afraid to face the mysteries lurking behind that valve cover? Don’t worry. Just follow these steps, and we’ll leave the night light on for you.

Step 1

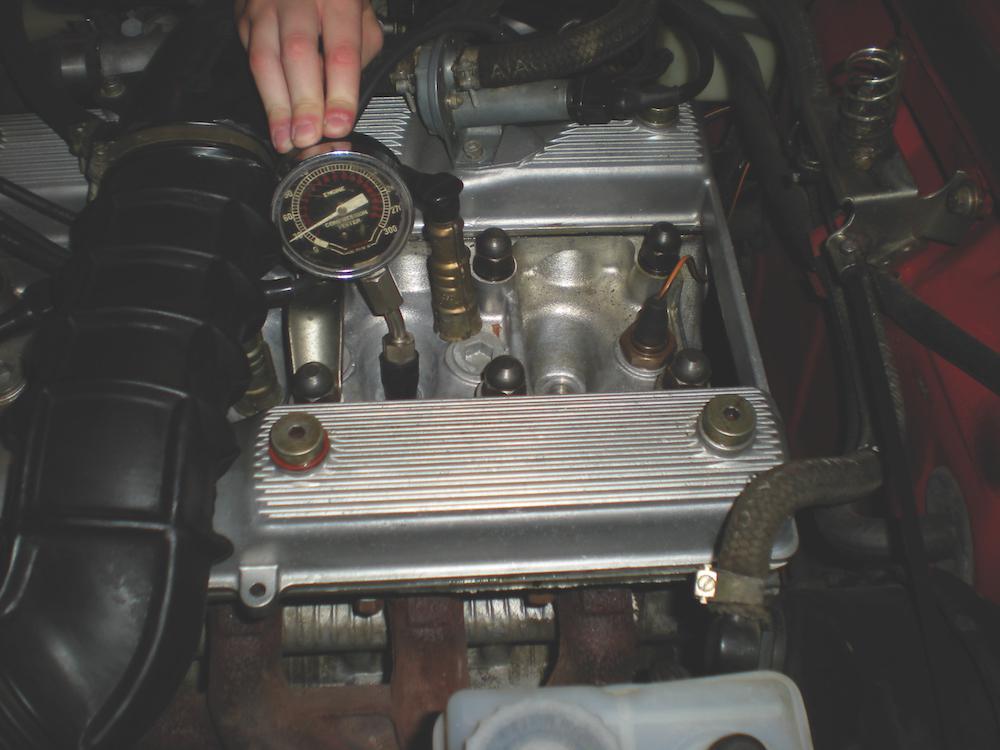

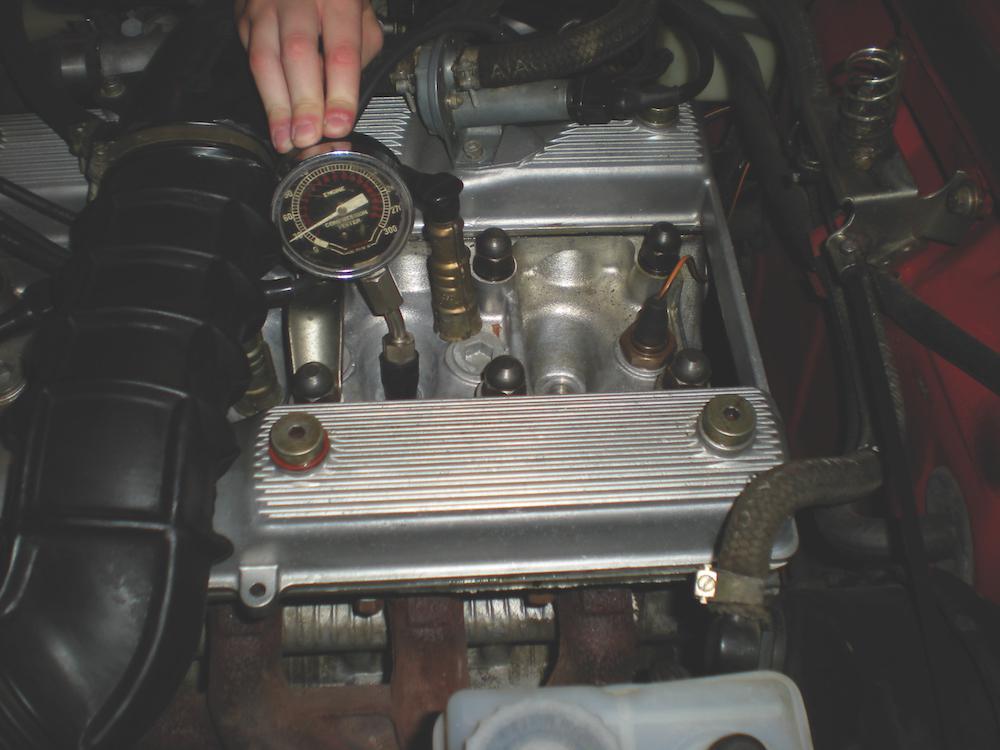

We knew our engine was down on power and suspected the culprit lay in the head. We wanted to diagnose the problem before tearing things apart, so we started with a traditional compression test.

Three of the cylinders were at about 150 psi, but No. 3’s reading of 30 psi indicated trouble. Because only one cylinder was down on compression, we suspected a burned valve.

If two adjacent cylinders had been similarly low on compression, we’d have suspected a blown head gasket between them. Another common issue with blown gaskets is coolant leaking into the combustion chambers; that one’s better diagnosed with a leak-down test.

Step 2

We started disassembly by pulling the plug wires, air intake tubing, valve cover and nearby sundries. That complex array of hoses and connections can be a pretty daunting sight, especially when you’re also worried about properly timing the cams.

Our approach is pretty straightforward. We pull out the service manual first and read it carefully—often several times. As we take things apart, we continually check the book to make sure we’re on track.

Perhaps more than the manual, we rely on our digital camera: We use it to snap dozens of photos from multiple angles. If something in the manual isn’t clear, we’ll have these pictures to guide us.

Step 3

Now that we’ve extolled the virtues of the service manual, we’ll admit it: We often defer to experienced opinions or improved methods. While Internet forums can sometimes offer quality information, use them with caution. How do you know Cam_Dude69’s advice has been vetted in the real world?

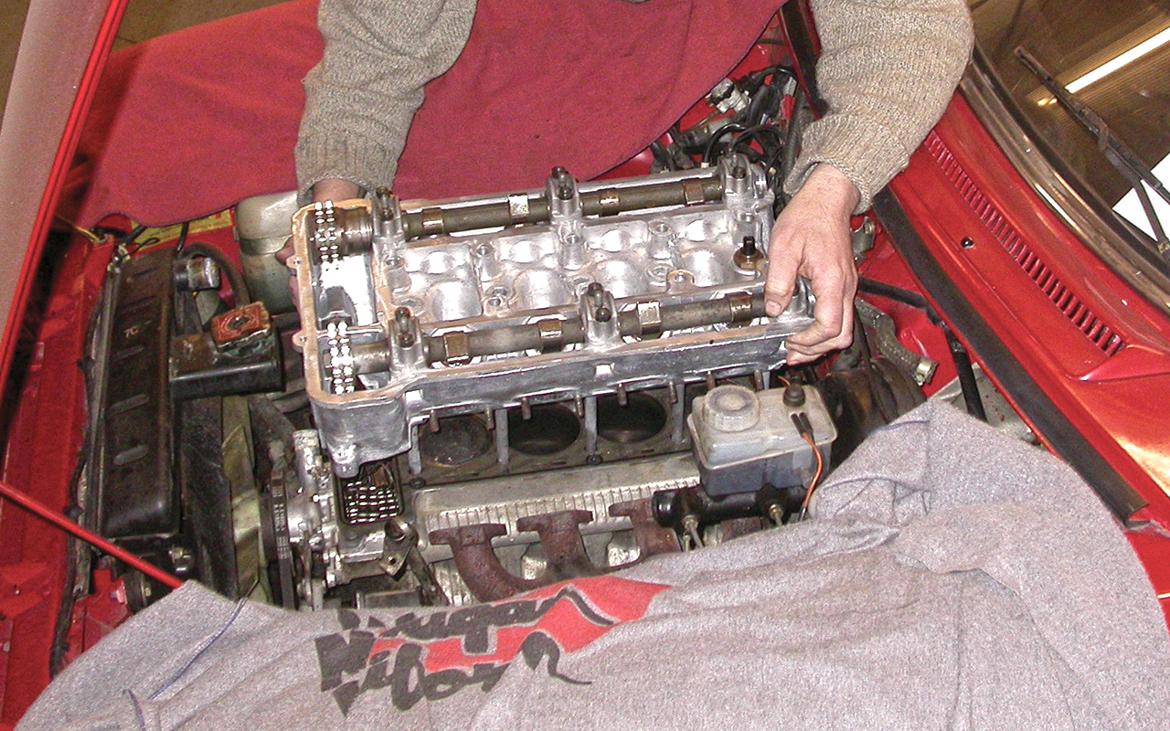

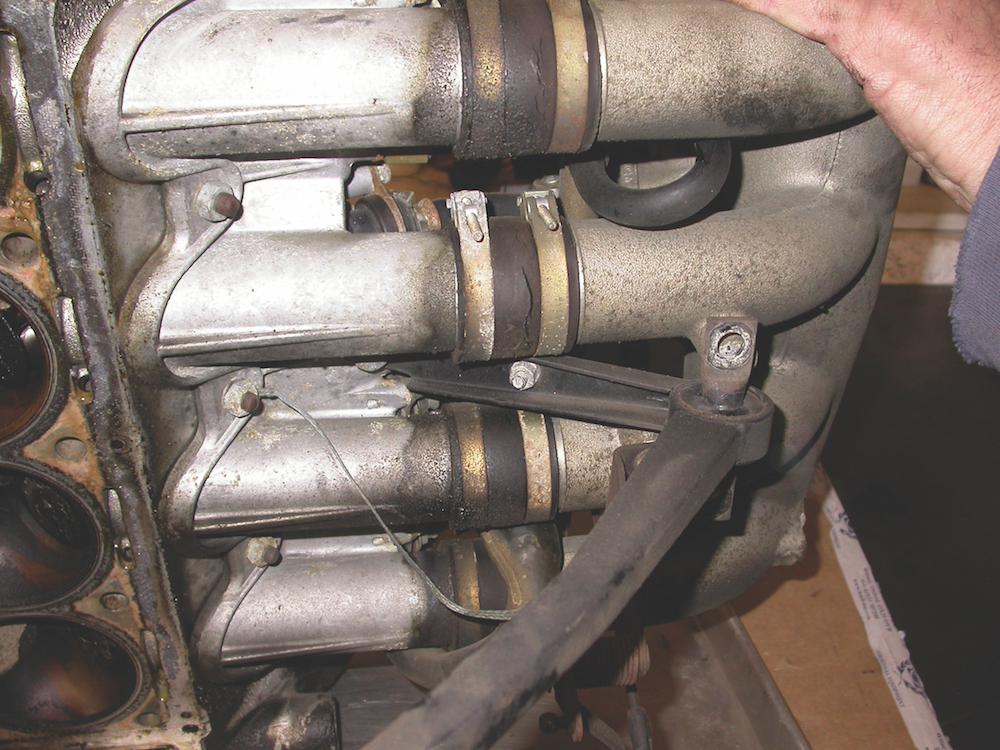

We knew from our own experience that removing the Alfa head with the manifold intact would save us a bunch of time. After securing the chains so they couldn’t fall into the sump and removing the head nuts, we pulled everything as a unit. We then continued the disassembly and inspection process on the workbench.

Step 4

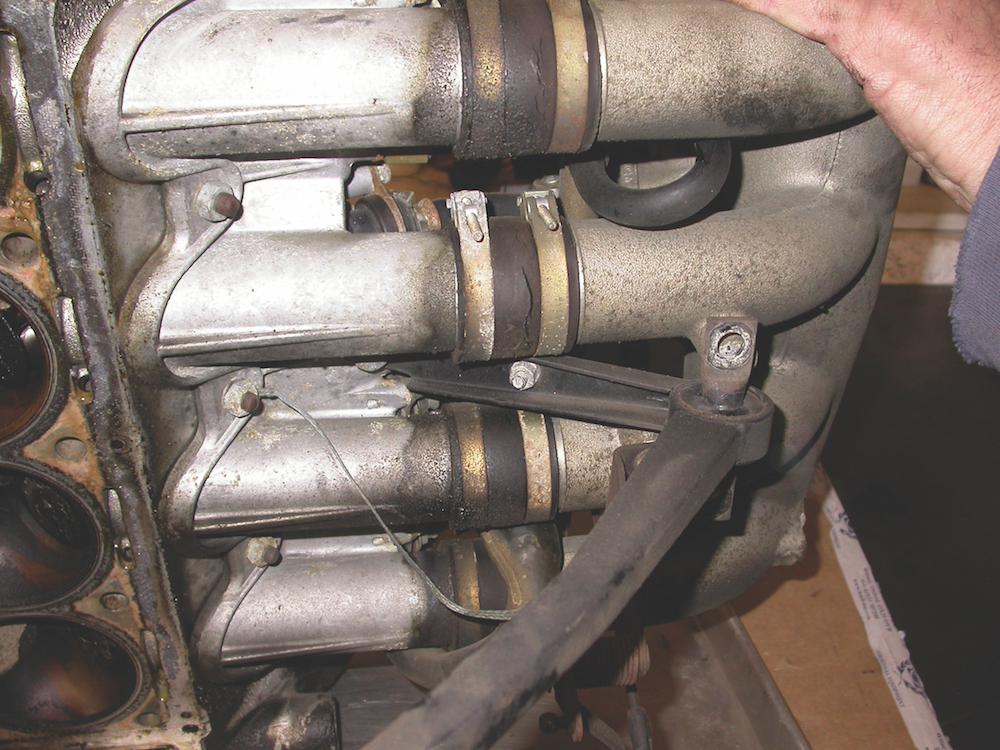

Our visual inspection of the intake hoses showed they need replacement. Furthermore, the cracked No. 3 hose might have caused a lean condition that burned our valve.

Step 5

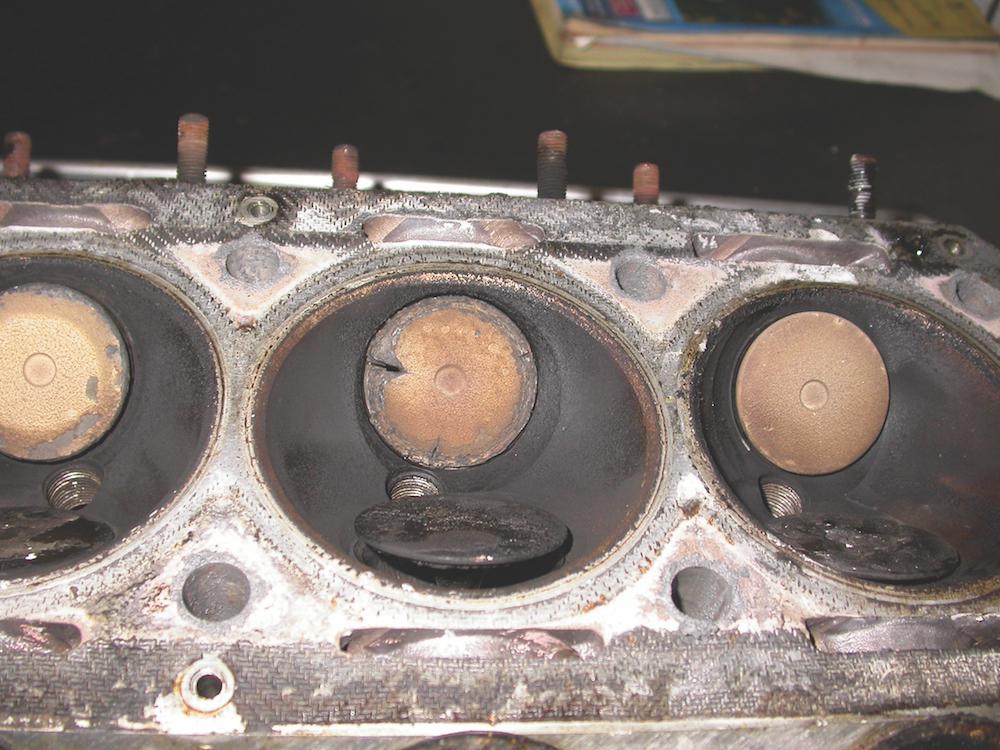

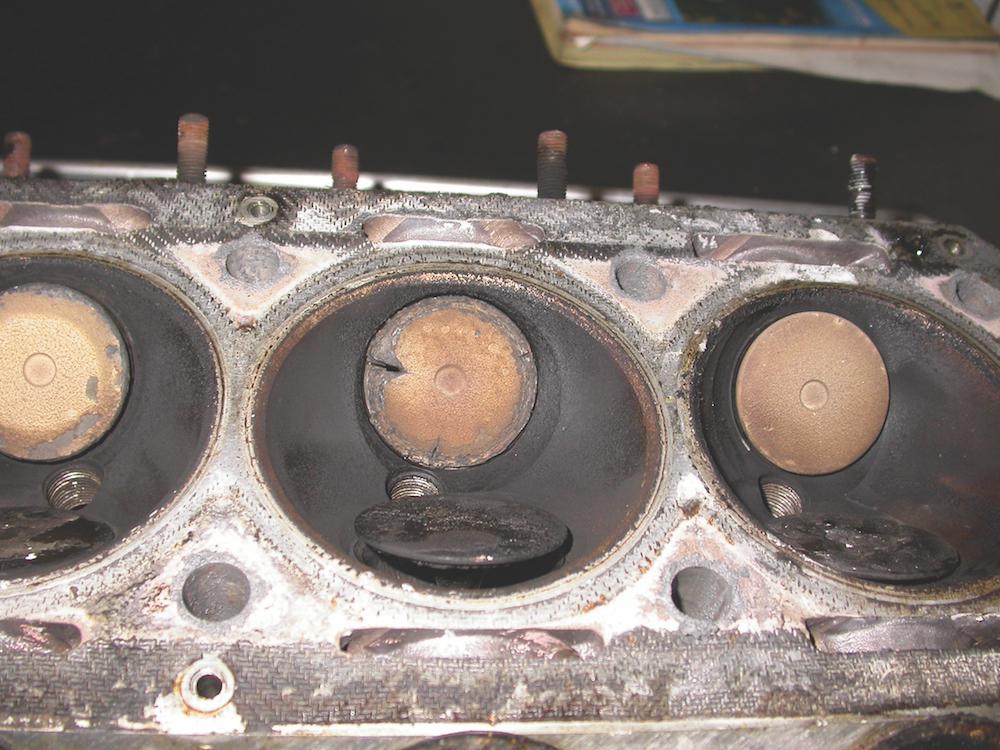

After we looked at the No. 3 exhaust valve, there was no question we needed to pull the head: The valve was clearly burned and was causing our low compression. It’s not always this easy to spot damage on valves. Sometimes it’s much more subtle and can only be revealed through further disassembly and testing.

Step 6

We sent the head to our local machine shop, CD’s Engines. The head wasn’t cracked, they reported, but it would need a full makeover with new valves, guides and springs. We ordered the necessary components from Centerline Alfa and got CD’s going on the headwork.

Step 7

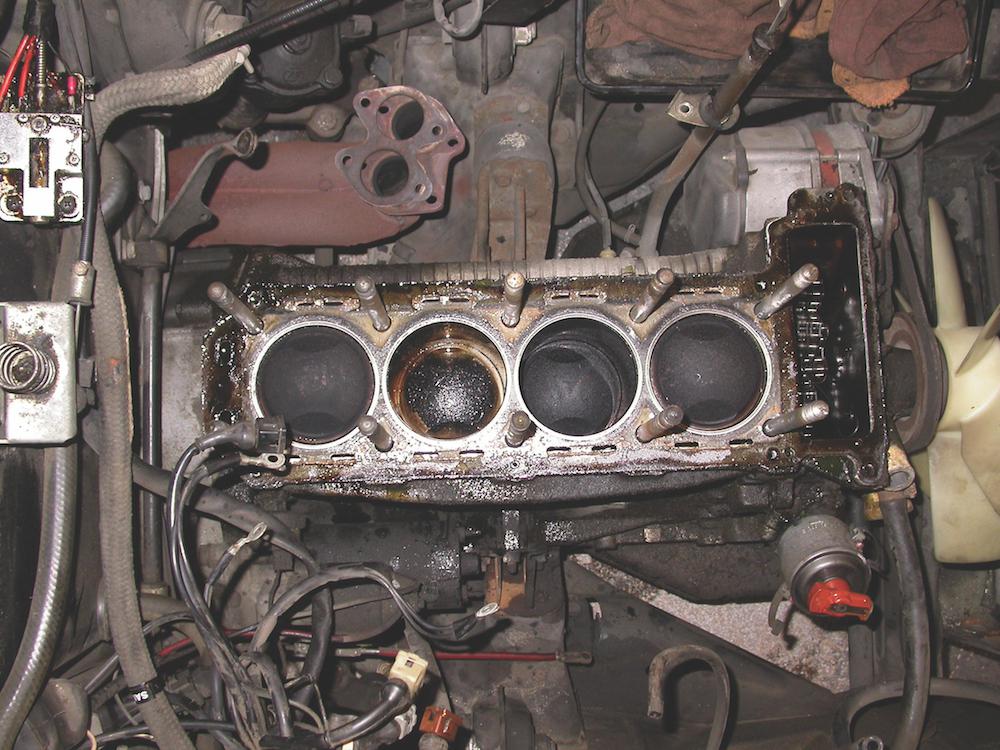

While the head was in the shop, we took the opportunity to clean our filthy engine and bay.

Step 8

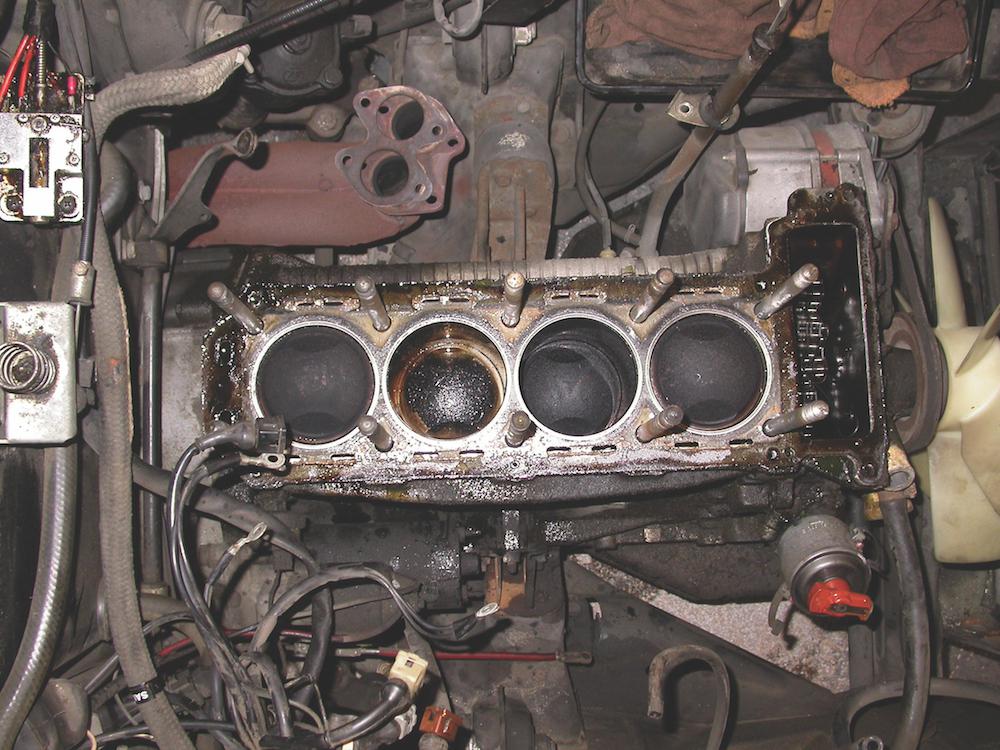

A lot of time with solvent, paper towels and brushes yielded some impressive results. After cleaning, we carefully checked the deck surface of the block with a straightedge to make sure it wasn’t warped.

Step 9

The head was spotless and ready for installation when it came back from the machine shop. CD’s also took care of the valve adjustment, as this Alfa head uses shims rather than self-adjusting hydraulic tappets. You’ll pay a bit more if the machine shop does the work for you, but it’s often worth it to reduce the hassle, especially if the job calls for special tools.

Step 10

When we send our cylinder heads for service, we typically ask the shop to do what they can to improve flow. In the case of this Alfa head, however, the factory ports were so nice that they didn’t require any extra attention. In fact, many modern cars can skip the prep work thanks to the excellent CNC machining done at the factory.

Step 11

Now that the new head gasket was in place, we could carefully lower the head into position on the block. We decided to leave off the manifold as we installed the head: It may be easier to pull everything as a unit, but reassembly is best done piece by piece. It takes longer, sure, but it allows us to be a bit more careful and precise during the process. That way, nothing gets pinched, blocked or mislocated.

Step 12

After reinstalling the head, we did the initial torquing of the head nuts. Next, we timed the cams and reconnected the chains according to the procedures detailed in the service manual. These may be tedious jobs, but they’re not difficult. We always take the time to double- and triple-check our work, especially if we’re dealing with an interference engine.

Step 13

Using our memory, our photographs and our manual, we put the components back on the engine, bit by bit. We took the time to clean each piece and replace any old components or hoses. Our goal, of course, was to have nothing left over at the end, and we succeeded.

Step 14

No matter the name on the valve cover, our post-headwork starting procedure is always the same. Before firing up the engine, we turn it over at least two full revolutions by hand to ensure there are no interference issues with the valves.

We then restart the engine as though it’s a new one. We build oil pressure by spinning over the engine with the plugs out, then replace the plugs and start the engine. We run it at 2000 to 2500 rpm, watching for leaks and other problems. Once the engine is fully warmed, we shut it down and retorque the head nuts. Finally, it’s time for a drive. Our work is done.